North Texas Wild: Local conservationists are bringing back the Blackland Prairie

A prairie remnant at Winfrey Point overlooking White Rock Lake in Dallas. Photo by Sean Fitzgerald.

Tallgrass Prairie, on the other hand, is a riot of life. Immense strappy leaves of big bluestem, eastern gamagrass, Indiangrass and switchgrass shoot up to five feet or more and arc to the ground. Between those clumps flourish little bluestem and sideoats grama, and beneath them shorter blue grama. Native grasses mature into mounds, some four feet across, others mere tufts. The prairie profile undulates, a low rounded leafy landscape, until autumn when stalks of feathery seed heads shoot up several feet to shine golden in the sunlight.

Tallgrass Prairie, on the other hand, is a riot of life. Immense strappy leaves of big bluestem, eastern gamagrass, Indiangrass and switchgrass shoot up to five feet or more and arc to the ground. Between those clumps flourish little bluestem and sideoats grama, and beneath them shorter blue grama. Native grasses mature into mounds, some four feet across, others mere tufts. The prairie profile undulates, a low rounded leafy landscape, until autumn when stalks of feathery seed heads shoot up several feet to shine golden in the sunlight.

Settlers heading west a few centuries ago wrestled their way through the vast eastern forests, crossed the Mississippi River and soon found themselves in the sun-kissed expanse of wide-open prairie. No need to clear trees from the land for farming or development. Settlers set plows to the virgin sod with rabid enthusiasm. Within a century, the Tallgrass Prairie was plundered. Now less than 1 percent remains. It is the most endangered ecosystem in North America.

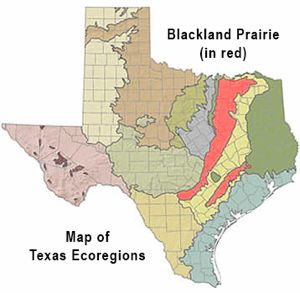

Map courtesy of the Native Prairies Association of Texas.

Plow, disk or bulldoze the prairie and it is destroyed. The prairie soil is a tightly networked matrix of mineral, humus, bacteria and fungus that took tens of thousands, even millions, of years to develop. When exposed to air and sunlight all that sunders. Above ground disappears a prairie community of plant, animal and insect species, interwoven in their dependency upon each other, that took many centuries to form.

The Blackland Prairie of North Texas

It’s a quixotic quest to save what little prairie that remains. For some people, all grassy fields are the same. They don’t step from their car and walk the prairie, see it up close, smell the richness of the soil, taste the prairie clover. They’re not startled by birds bursting from the grass and don’t hear the rampant wildlife skittering through its leaves. They miss the tiny wildflowers flourishing in the shelter of larger grasses and the myriad of butterflies and bees they feed. A tallgrass prairie is rainforest thick and just as wild.

Deep, dark, rich, fertile clay soil identifies the Blackland Prairie — the most endangered type of Tallgrass Prairie. It stretches from the Mid-Cities to the East Texas pine forests in a wedge down to the Hill Country. Dallas and its suburbs arose on the Blackland Prairie. A few parcels linger, like the petite, picturesque Frankford Prairie in North Dallas and the rangy 50-acre Parkhill Prairie in northeast Collin County. Comparatively big, but small by original prairie standards, is the 1,400-acre Clymer Meadow in Hunt County — one of the largest blackland parcels in existence.

Deep, dark, rich, fertile clay soil identifies the Blackland Prairie — the most endangered type of Tallgrass Prairie. It stretches from the Mid-Cities to the East Texas pine forests in a wedge down to the Hill Country. Dallas and its suburbs arose on the Blackland Prairie. A few parcels linger, like the petite, picturesque Frankford Prairie in North Dallas and the rangy 50-acre Parkhill Prairie in northeast Collin County. Comparatively big, but small by original prairie standards, is the 1,400-acre Clymer Meadow in Hunt County — one of the largest blackland parcels in existence.

Frankford Prairie is located on property where the Frankford Church and Cemetary stands in North Dallas. Photo by David Rogers.

Whizzing along eastbound Mockingbird in Dallas, just after passing White Rock Lake, you may never have noticed the mounded texture to the unmowed grass on either side of the thoroughfare or the abundance of varied wildflowers tucked amid the tufts in spring. Note the same appearance on the broad slopes that rise above the Bath House Cultural Center and Doran Park, and some expanses near Winfrey Point and Flagpole Hill. All remnants of the once immense Blackland Prairie.

In Tarrant County, a small remnant was also preserved in Arlington, now known as the 13-acre Blackland Prairie Park.

Quixotes of the Prairie

Native Prairies Association of Texas is on the front line of preserving prairies, and its Dallas-based Blackland Chapter meets monthly near the lake. The group of prairie enthusiasts listened in rapt attention in November as naturalist Becky Rader explained how the thin soil over chalk rock on the lake’s east side led to its use as a dairy farm rather than cultivation. The prairie ecosystem remained intact, albeit debilitated by intense grazing and haying. After becoming a park, it endured constant mowing, compaction from cars, and other indignities.

Native Prairies Association of Texas is on the front line of preserving prairies, and its Dallas-based Blackland Chapter meets monthly near the lake. The group of prairie enthusiasts listened in rapt attention in November as naturalist Becky Rader explained how the thin soil over chalk rock on the lake’s east side led to its use as a dairy farm rather than cultivation. The prairie ecosystem remained intact, albeit debilitated by intense grazing and haying. After becoming a park, it endured constant mowing, compaction from cars, and other indignities.

Prairie flowers at Clymer Meadow. Photo by RJ Hinkle.

Rader was one of the curious naturalists who noticed native prairie plants growing in the urban park. Joined by Texas Master Naturalists and others, their first step was to convince Dallas Parks and Recreation Department to simply stop mowing the areas. Once the plants regained their natural stature, Jim Eidson of The Nature Conservancy and other prairie experts came in to assess the rare treasures.

Then began the long course of action to restore the prairie patches. It’s a fine-tuned, hands-on process that does not always jive with DPRD maintenance budget and practices. Invasive non-native species must be curtailed and original Blackland Prairie ones re-introduced. Wildfires and roaming herds of buffalo once kept native brush like cedar elm and trumpet vine from taking over, so that must be done manually, too.

Starting in 2016, in cooperation with DPRD, prairie Quixotes, including the Blackland Chapter, will steward their own prairie patches. Having restored prairie parcels at a place northeast of Dallas called Osage Moon, I’ve learned to see a landscape come to life is soul rewarding. The land expresses gratitude with prairie abundance that in turn provides for a community of wildlife — life created solely because people chose to make a difference.

Walking the Prairies

Blackland is not the only prairie in North Texas. The Grand Prairie begins in the Mid-Cities, hence the suburb’s name, and reigns from Fort Worth westward. Its grasses tend toward hues of sage green and dark amber, and their shorter height make wildflowers easier to see. Strips of Eastern and Western Crosstimbers stretch vertically through the mid-Metroplex with patches of Post Oak Savannah and its short to mid-range grasses.

Blackland is not the only prairie in North Texas. The Grand Prairie begins in the Mid-Cities, hence the suburb’s name, and reigns from Fort Worth westward. Its grasses tend toward hues of sage green and dark amber, and their shorter height make wildflowers easier to see. Strips of Eastern and Western Crosstimbers stretch vertically through the mid-Metroplex with patches of Post Oak Savannah and its short to mid-range grasses.

Indian Grass at Amy Martin’s restored prairie, Osage Moon, in Fannin County. Photo by Scooter Smith.

Late autumn is the perfect season for prairie walks. The native grass seed heads are still buoyant, chiggers are nonexistent, and you can walk in full sunlight without getting too hot. The Blackland Chapter posts a list of local prairies on their website. Learn about prairies at the NPAT site, where you can also discover how to create or restore a prairie. The Fort Worth-based NPAT chapter also hosts speakers and hikes at local prairie remnants in Tarrant County.

The original prairie is living history; it holds our natural heritage. It asks you to turn inward and appraise what you take most for granted: the ground beneath your feet that the prairie holds in trust. At the same time it opens you up, for on the prairie the sky is half the landscape. With its expanseness, the prairie connects you to the cosmos in all its immensity, leaving you as a human suspended in the betwixt between for one short moment in time.

RELATED ARTICLES

Sign up for the weekly Green Source DFW Newsletter to stay up to date on everything green in North Texas, the latest news and events.Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest.

Original post at: http://www.greensourcedfw.org/articles/north-texas-wild-local-conservationists-are-bringing-back-blackland-prairie