The River and the Wall: Ben Masters documentary focuses on Rio Grande

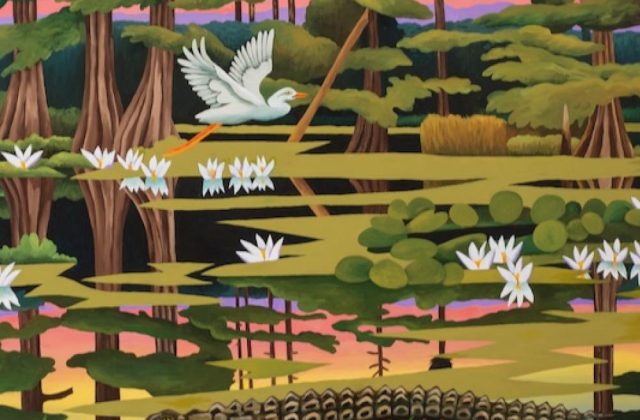

‘The River and the Wall’ will screen during the EarthxFilm festival on April 25 at the Perot Museum. Photos courtesy of Fin and Fur Films.

March 6, 2019

The Rio Grande is not just the border. It is the center — of a culture, an ecosystem, a watershed, a woven history that arose well before national borders and will continue long after the artifice has gone.

Conservation filmmaker Ben Masters lets the river tell its own story in the feature documentary The River and the Wall, along with the stories of five who travel its length in Texas. They embark in El Paso for a 1,200-mile immersive journey downriver by boat, bike and horse, through riparian wilderness and urban valley culture, enduring moments ranging from harrowing fear to awestruck bliss. The epic excursion ends at the Gulf of Mexico.

The River and the Wall is both an adventure/road film about traveling through a spectacular landscape and a penetrating examination of the ecological and cultural ramifications of a border wall.

The River and The Wall – 2017 Trailer

“It’s a two and a half month trip down the Rio Grande documenting the borderlands and landscapes the river goes through. I wanted to know how a physical wall would impact the wildlife and people that live along the border,” said Masters.

The River and the Wall premieres at SXSW on March 9. EarthxFilm screens the film at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas on April 25.

“People are in denial. They think the wall’s not going to happen. But it’s happening right now,” said Masters, referring to the partial destruction of the National Butterfly Center. “What a wasted opportunity it would be not to document the fourth longest river in North America, the Rio Grande, before it got walled off.”

In the film, five travelers – a wildlife biologist with a focus on birds, a Guatemalan-American river guide from Terlingua, a nature activist with deep credentials, a naturalized Brazilian immigrant turned television celebrity, and Masters – bear witness for a land that cannot speak for itself, before a tragedy of irrevocable impact unfurls.

STORYTELLER

Masters, a red-headed horseman with a wry Texas drawl and great stubble, planned to find work as a scientist after gaining a degree in wildlife biology from Texas A&M.

“What I saw was a lack of storytellers in the science and research fields. I decided instead to make films on wildlife and wildlife habitat, to show stories that matter to me and so would matter to others.”

Two years in the making, The River and the Wall is Masters’ first full-length film as a director.

“As for style,” said Masters, “it’s similar to Unbranded, directed by my friend Phill Baribeau because he’s the best filmmaker that I know. The sincerest form of flattery is imitation, so I started to do what he did.”

Before this, Masters created character-driven shorts on conservation for his Fin and Fur Films, with three of them focused on the Trans Pecos: Pronghorn Revival, Lions of West Texas and Wildlife and the Wall. A former horseback guide in Yellowstone National Park, he’s best known for his work on Unbranded that explores preservation of the wild mustang. He and a trio of cowboys rode mustangs they adopted and trained from Mexico to Canada. Masters, 30, splits his time between Texas and Montana with his wife, Katie.

Wildlife and the Wall | WILDxRED

“The big inspiration for The River and the Wall was that I spent a lot of my life on the border,” said Masters, who lived some of his teen years in San Angelo. “Since I was in high school, I’ve worked on ranches in South and West Texas. It’s a landscape misrepresented in media.”

Masters’ intimate knowledge of the landscape, the seasons and the way western sunlight works the terrain, allowed him to find astoundingly beautiful shots. His relaxed camaraderie and authentic western ways fostered an easy dialogue with border inhabitants on both sides and kept the cast and crew’s spirits up.

“Everybody came on board in a fortuitous manner,” said Masters. “Jay Kleberg [associate director of Texas Parks & Wildlife Foundation] and his family have a history on the Rio Grande for two centuries. I met Austin Alvarado and Heather Mackey out in the Big Bend when I was filming star lapses. They rode by on bicycles. I had beer, and they didn’t, so we became friends. Austin is a river guide, so that’s a pretty cool skill set to have on this journey, and Heather is an ornithologist, so she did bird counts during the whole trip, creating a baseline of data.”

“Filipe DeAndrade [star and producer of National Geographic’s Untamed], he’s a fellow wildlife filmmaker and was an immigrant who came from Brazil as a child. He was undocumented for 14 years. So we go into his past and what it’s like to live like that in the United States.”

The life stories of Alvarado and DeAndrade weave through the film and humanize the immigration debate. It’s this profound, intimate angle that pushes The River and the Wallbeyond what prior traveling Rio Grande reporters – Dan Reicher, Collin McDonald (Disappearing Rio Grande Expedition), and Keith Bowden (The Tecate Journals) – were able to do.

“It’s a pretty personal movie. You’re going to get totally sucked into different people’s backstories. We travel across time and dig into the history of the border wall and immigration. It’s a deep dive into the topic.”

The soundtrack by Noah Sorota, with its classical guitar and 20-musician orchestra, emphasizes the cross-cultural ensemble.

“A big cinematic score. A Southwestern flavor with Central American percussion, very borderesque. It’s bad ass,” said Masters.

GRAND RIVER

An artery of water that connects the Rocky Mountains of southern Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico, the Rio Grande embodies a myriad of personalities along its length. Born of snowmelt, it courses and tumbles the distance of New Mexico from peaks to foothills. It flows through valleys where agriculture and industry drain it of water.

By the time the Rio Grande reaches El Paso, it’s dubbed the Rio Sand, a trickle of water diverted into a concrete channel. Masters and company rode mountain bikes through this area, close to an existing border wall that accedes the river to Mexico.

“Where there wasn’t enough water,” said Masters, “we used bicycles and my horses. I have some badass mustangs and was wintertime. They were happy to leave Montana.”

South of El Paso, the Rio Grande aridly oozes through the Forgotten Reach, a section of stringent desert with no people, no power, no cell phones, nothing at all but forlorn vastness. A fine place for frozen mud to lock up the mountain bikes’ gears, forcing travelers to tote them for miles in frigid, wet wind.

Once to the Big Bend area, run-off from the Davis and Chisos Mountains on one side and the Sierra Madre on the other resurrects the river, enhancing habitat for black bears, bighorn sheep, pumas, bobcats and birds. It surges again between the steep rock walls of Big Bend Ranch State Park and Big Bend National Park.

In Big Bend’s lower canyons, including Boquillas and Mariscal, the river becomes raw and turbulent. Here the travelers switched to canoes. This section and some additional Trans Pecos mileage downriver enjoy protected National Wild & Scenic Riverstatus.

“We ended up multiple times in the rapids. It’s all fun and games,“ said Masters.

Floatable waterproof tethered containers called pelican cases protected the cameras.

“The lower canyons are one of the most amazing landscapes on the face of the planet,” said Masters.

It’s a concentrated essence of geologic time where bird calls reverberate endlessly, more intimate than the Grand or Palo Duro canyons. Here the Rio Grande merges with rock, caressing yet eroding it, leaving mysterious pocks and curves. Time becomes timeless.

BI-NATIONAL ECOSYSTEM

“People look at the Big Bend and they see all those public lands. They think that that’s where it stops,” said Masters. “But the really big intact habitat is in Mexico. They have three million or so acres of protegidas, which are like conservation easements.”

A primary protegida owner is Mexican construction mega-corporation CEMEX that has a deep interest in bighorn sheep reintroduction. The former ranches are now managed as preserves in perpetuity by the government.

“If you combine the protected lands of Mexico with those of the United States in the Big Bend region,” said Masters, “you have an area of intact Chihuahuan desert habitat nearly twice the size of Yellowstone. Huge elevation changes, massive mountains, ponderosa. It’s incredible.”

Such a massive mountainous ecosystem pays no heed to human borders, nor does the wildlife that inhabits it. But to the people who live there, the river-as-border entirely shapes their lives, culture and personalities.

Masters observed how the citizens of Mexico treasured the Rio Grande in the way that a river lifeline in a desert landscape deserves. In Big Bend and other places, it’s a scene of river recreation (boating, fishing, swimming) and leisure (sports, picnics, family gatherings). On the American side: mostly border patrols.

Since the 1930s of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, naturalists have dreamed of a bi-national park recognizing the vast ecosystem anchored by the Rio Grande watershed.

“I can’t think of a more beautiful olive branch between the two countries than to conserve an ecosystem together like the U.S. and Canada did with Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park. I’d love to see it happen. I think most people would. But it would require a different way of looking at the border,“ said Masters.

IMPERILED BEAUTY

South of the scenic river section, past the second deep curve that makes the Big Bend, the Rio Grande receives a watery boost by the Pecos River and burbles through the stark and pictograph-graced Pecos Canyonlands.

The Rio Grande is dammed north of Del Rio to create 64,900-acre Lake Amistad, Spanish for friendship. Lake Amistad National Recreation Area sprawls for an additional 58,500 acres along the tributaries and Rio Grande. Fierce headwinds on the giant body of water forced Masters and company to portage past the dam. It is here Masters found a great surprise:

“The stretch of the Rio Grande that stuck with me and I intend to keep going back to is south of Lake Amistad. The river travels for 30 to 50 miles through beautiful limestone cliffs similar to the Devils River country. Huge flocks of white pelicans fly up and down the river. In the wintertime, massive flocks of ducks come bursting out of the cane and reeds.”

“The scenery rivals anything you’d find in the Hill Country, but there’s a massive amount of water and excellent birding. Just gorgeous. The beautiful thing about canoes, traveling the speed of the river, soaking up the landscape at three miles an hour, it gives you a lot of time to think and ponder and reflect. Just you and a paddle and bird watching and listening to the sound of the current. It’s awesome.“

Yet the Rio Grande is imperiled. Ecologists maintain that a border wall would devastate natural life. American Rivers recently returned the Rio Grande to its annual most-endangered rivers list. Over 90 endangered species (verified or suspected) will be seriously threatened by a border wall, according to the Center for Biological Diversity .

By the end of The River and the Wall it’s clear. While it is a river of many personalities and segments, it is more accurately the vital artery of a watershed whose fluid strands connect diverse ecosystems, cultures and governments to create something whole unto itself. Its future existence depends on it being approached holistically.

WILD SIDE OF RIVER

Not all the wildlife in The River and the Wall was four-legged or feathered.

“I don’t want to give any spoilers,” said Masters. “You’ll have to wait and watch the movie. Let’s just say we ran right into the middle of the human element of the drug and human trafficking side of the immigration debate.”

Another issue was technical, said Masters:

“Our drones kept flying to Mexico! We’d send a bird up in the air and I don’t know what was going on, radio frequencies or jammers or something weird going on at the border. You take a perfectly fine drone and send it up over the Rio Grande and weird stuff happens. Lost two drones, which is a shame. I’d love to have the footage.”

TRUE COST OF THE WALL

From Laredo to Brownsville, the wilderness recedes to urban development. The travelers went overland on mountain bikes along the border wall constructed under President George W. Bush, an area slated for increased construction by the current administration.

The River and the Wall examines how the wall would function in the lives of border residents, taking in views from farmers and ranchers, naturalists and wildlife biologists, border patrol agents and social workers, and politicians including U.S. Representative Will Hurd, a Republican, and former Democratic U.S. Representative Beto O’Rourke.

The film makes it clear how far into American land the border wall intrudes, seizing thousands of acres by imminent domain, severing people from their property, essentially ceding vast swaths of Texas as well as the entire river to Mexico. The source of water humans and wildlife in the U.S. depend on will no longer be accessible – deadly in a desert region. Yet a wall will dissuade only a few trespassers and delay those who do cross from Mexico by mere minutes (it took the film crew less than 10).

THE ROAD GOES ON

Once again, the Rio Grande’s vibrant ecosystem shone through. Masters and crew found themselves enthralled by the bounteous tropical birds of the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

The group returned to the Rio Grande for the last ten miles, canoeing through giant stands of invasive river cane to reach the Gulf of Mexico.

Masters did come to one conclusion for his next film: “I will not be going in hot-air balloons and I will not be going in bicycles. I like canoes and I like horses and I know what I like. I’ll stick to those.“

The River and the Wall

Premiere: The film debuts at SXSW Film at the Alamo Ritz on March 12 and the Paramount Theater on March 15. Film team and film subjects will be on hand. Tickets.

Local Screening: April 25, EarthxFilm is showing the film at the Perot Museum of Science & Nature

National Release: Film distributor Gravitas Ventures plans to release documentary beginning in late spring to more than 100 theaters nationwide.

Film Guide Book: The River and the Wall with photography and text by Ben Masters and co-contributors. Sponsored by The Meadows Center for Water & the Environment’s River Books, and published by Texas A&M University Press, it releases on April 18.

“We wrote a book that dives deeper than we could in the film into a lot ofthe Rio Grande and border topics. It is also is a visual journey. Something that often struck us on the trip was that a lot of the images we were taking could be some of the last before the border wall. So we tried to include a plenty of aerial and land photography in the book,” said Masters.

Stay up to date on everything green in North Texas, including the latest news and events! Sign up for the weekly Green Source DFW Newsletter! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Original post at: https://www.greensourcedfw.org/articles/filmmaker-portrays-beauty-region-be-cut-wall