Rookery thrives within Dallas medical district

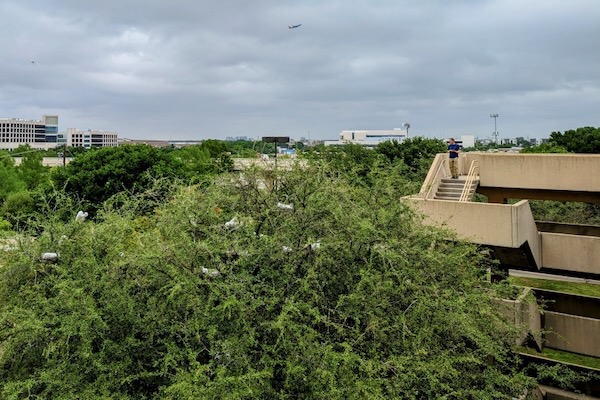

UT Southwestern Medical Center surrounds a large active rookery in the heart of the Southwestern Medical District, north of downtown Dallas. Photo by Mei Ling.

Original post at GreenSourceDFW.

By Amy Martin — April 28, 2023

When it comes to some nesting birds, there’s no place like home.

That’s what Sam Kieschnick, urban wildlife biologist for Texas Parks and Wildlife, says led to a large heron and egret rookery ending up nestled in the Southwestern Medical District, north of downtown Dallas.

Like a pilgrimage, the birds return annually to this heavily wooded vale on the south campus of UT Southwestern Medical Center to breed and raise their young. They reuse nests or the nesting material.

The scientific term for this parental drive is “nest fidelity.”

Meanwhile, thousands of cars pass daily on nearby Inwood and Harry Hines Boulevard. Only the alert notice the big birds flying overhead, destined for the Trinity River nearby.

ROOKERY TOUR

I’m spending a morning ambling a trail that skirts the rookery with Kieschnick. About 25 of us follow him on this UTSWMC-sponsored excursion as he shares fun facts and observations about the birds and rookery.

“February is when some smaller birds like the yellow-crowned night heron or the black-crowned night heron arrive. They are the scouts. They’re looking for the right spots in the rookery they were born at or another potential site, ideally nearby,” says Kieschnick. “By July and August, this place is rockin’. So we’re not getting the full effect of the summer smell.”

UTSWMC’s been in the area since 1943 and references to the birds pop up in their history. The state’s oldest bird group, Texas Ornithological Society, has records of birds breeding here since 1966, but it no doubt dates back much further.

Wedged between hospital buildings and parking garages amid endless pavement, the wide ravine home to the rookery gives stormwater rushing off concrete somewhere to go, creating wet, fertile woods.

AVIAN RESIDENTS

Our group treads the half-mile loop that skirts the rookery edge through a grove of gnarly post oaks dotted with cedar elms. Signs along the woods’ edge warn against trespassing into the rookery core. A wide tree-lined ravine that disappears into underbrush and darkness, it’s densely wooded with cottonwoods, hackberries, oaks and more.

These post oaks are home to the rookery’s suburban birds. We view a scattering of tall great egrets with dramatic white plumage, snowy egrets, night herons and anhingas perching in the post oaks or striding beneath. Occasionally we can peer through the leafy branches and spy large stick nests in the canopies. In the treetops are many dozens of nests we can’t see.

“I saw some snowy egrets out here doing a dance this morning, impressing or fighting each other off. It’s hard to tell — romances are like that,” jokes Kieschnick.

Unseen but heard in the rookery core are hundreds of those birds, plus little blue herons and even tri-colored herons.

Joining tham are petite cattle egrets and exotic white ibises with their showy pale eyes and long, curved orange beaks. Occasionally one will emerge and fly off toward the Trinity River, seeking fish for their young.

“Anhingas are a weird bird,” says Kieschnick. “They’re pretty much solid black. They keep their really long neck curled up. When they’re hunting, they’ll stick that thing out straight, giving them the common name of snake bird. It’s actually more of a coastal bird. Not too common in DFW.”

Little blue herons and white ibises are uncommon and exciting to see. Photos by Tracey Fandre.

To stand and stare at courting and nesting birds at such close quarters could be considered a threat. So we stay quiet, be unobtrusively observant and keep moving, never pausing beneath nests (which is risky anyway). Photographers stop to take a few pictures and move on. We step away from the birds for educational discussions.

“My favorite spot is on the top of the parking garage where I can catch them in flight and see down into the nests. You’re at a distance that doesn’t disrupt or disturb them,” says Garland-based wildlife photographer Tracey Fandre.

Indeed, the topside view is stunning. Large stick nests can be spotted in the tree canopy, occupied by big birds — an arboreal sea of green, dotted with white.

Enjoy this video to see the rookery in action shot by Scot Miller for CBS Sunday Morning.

CIRCLE OF LIFE

Sam stops by the decaying carcass of an anhinga on the ground next to the UTSWMC parking garage.

“So let’s talk about death. I know, welcome, good morning. Death is so important when it comes to nature. When something dies, those nutrients nourish the ecosystem. So when you see a dead or dying bird, it pulls on your heartstrings,” says Kieschnick.

“This is an area where if a bird is dying, the best thing you can do is allow it to die. And this is so hard. But those nutrients are used to fertilize the ground. The bodies feed all of the raccoons, bobcats and coyotes. They’re used to feed the fungi to feed the little tiny insects. All of those utilize the resources.”

A walker asks what the birds eat.

“These guys are opportunists, and they’re rather carnivorous in this stage,” Kieschnick replies. “They prey on baby squirrels, other birds, rodents, snakes, whatever they can find. The chicks eat mostly fishes brought by their parents.”

Another asks why the nests are so close together. Are they helping each other?

“Yeah, they might be kind of helping each other, extra eyes to look around. But they’re also going to be competing. Sometimes within the nest. In some cases, the brother kicks out the sister or vice versa, says Kieschnick.

The rookery does thwart trespassers.

“I don’t think there are any homeless camps under there. Not a pleasant place to live,” notes Kieschnick.

ROOKERY DOWNSIDES

The avian breeding melee doesn’t always engender many fans. The smell of dead birds and fish carcasses is not fun. In the heat of summer, the stench of prodigious bird feces wafts into the campus. The birds’ squawking creates quite a racket.

A former employee of UTSWMC recalled when the center wanted to take out the trees for development. Another time, there was a push to clear out the underbrush. Local birders, Audubon chapters and Texas Parks and Wildlife intervened.

Then UTSWMC rookery opponents tried to stoke fears of histoplasmosis, an infection caused by breathing in spores of a fungus found in bird droppings. But that’s only an issue within the rookery core where people are not supposed to venture.

Since then, UTSWMC has embraced the four-acre preserve, formally identifying it as a bird sanctuary and installing trails. Signs educate about the bird species and caution against bird harassment. The rookery even has a marker on Google maps.

“They can be beautiful things if contained. If not contained, it can be a problem, says Kieschnick.

When the city of Carrollton bulldozed a rookery in a residential area during nesting season in 1998, a federal violation, the carnage of dead and dying birds created a public relations nightmare they have yet to live down.

UTSWMC contains the rookery and lessens nesting sites on the fringe by trimming trees to prevent Ys where birds can lodge nests.

VISITING THE ROOKERY

The rookery trail system is visible on Google maps. Search for “UTSWMC Rookery.”

The rookery is located in the south quadrant of the Inwood and Harry Hines Boulevard intersection. The address is 2000 Inwood Road in Dallas. Turn on UT Southwestern Drive and take an immediate left on Campus Drive. Look on the right for the small three-car parking niche. If full, double back and park along UT Southwestern Drive.

A paved trail leads from the parking niche to a memorial garden. The stone monument reads: “In memory of those who have so graciously helped further the advancement of medical science.” A bird identification sign is nearby.

A short loop trail goes around the monument and through the grove. Walking clockwise from there, the trail goes along Campus Drive through the post oaks, curves along a driveway and skirts the South Campus Staff Parking Garage. Look for a trail spur connecting to stairs to the roof and an overhead view of the rookery. The trail continues to Hutchison Drive but curves along the woods and heads to a large pavilion. Trace along UT Southwestern Drive back to the parking niche.

RESOURCES

• Google Maps. The rookery trail system is visible on Google maps. Search for “UTSWMC Rookery.”

• UTSWMC map. The rookery is located at Inwood and Harry Hines, where the map is marked SOUTH CAMPUS.

RELATED ARTICLES

Wild bird expert was leader in local rehab community

Dallas medical district renovation to follow green prescription

Unpaving Paradise: Returning nature to a Dallas medical district using high-tech design

North Texan makes top 10 list on popular naturalist app

Stay up to date on everything green in North Texas, including the latest news and events! Sign up for the weekly Green Source DFW Newsletter! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter. Also check out our new podcast The Texas Green Report, available on your favorite podcast app.