Residents got rid of Shingle Mountain. Is a park in their future?

The Floral Farms neighborhood in South Oak Cliff seeks to create a community green space on a former industrial dump site.

Marsha Jackson and advocates for her South Oak Cliff neighborhood embody their slogan, “Together, we can move mountains.”

A year ago, they forced the removal of Shingle Mountain — a six-story pile of shredded shingles weighing more than 150 tons — from behind Jackson’s residential street in the Floral Farms neighborhood, near Interstate 45 and Simpson Stuart Road.

But to Floral Farms residents, removing the giant pile of refuse is not enough to make things right. They seek a clean-up of the lead-saturated site and testing of residents for asbestos and other shingle dust health issues.

But more than that, they want their neighborhood back.

“Floral Farms is home to three major nurseries that supply plants and flowers not only for the Dallas area, but also state wide and nationally, some of them with a history dating back to the 1920s,” said Jonathan Soukup of Southwest Perennials, one of the greenhouses in the community. “These are the folks who are actively working to make our world a more beautiful place, working to make our lives more green, yet their community is being used as a dumping ground for every undesirable venture in the city.”

FLORAL BEGINNINGS

In the 1950s, Floral Farms arose on the edge of the Great Trinity Forest, just south of its older sister cities Joppa and Bonton.

Drawn by the agricultural zoning, an African American and later Latinx rodeo culture flourished. DFW Trail Riders Association is still active here. Farms and greenhouses grew flowers, produce and nursery plants, giving the area its name.

Floral Farms spread out from SH 310, formerly the southern gateway to Dallas, later supplanted by I-45. Life centered around Joppa’s Lemmon Lake. Families held barbecues and picnics, fished in the lake and rode horses in the forest.

According to a 1992 Dallas Morning News article, the city annexed the area during the same period yet provided no services like trash collection, buses, water or sewers, even though just 20 minutes southeast of downtown Dallas.

Then flooding increased a decade or two later, exacerbated by rapid developments to the north that caused torrents of stormwater to rush into the Trinity.

Rather than implement sewers and swales that would direct the floodwaters, the city of Dallas temporarily ceased issuing building permits in the area. Buyouts of residents commenced in the 1970s, but the city ran out of funds.

Part of the community survived on the higher ground between SH 310 and I-45 east to the Trinity River. Floral Farms stretched from River Oaks Drive south to Youngblood Road, with Simpson Stuart at its middle.

In the 1980s, industrial zoning supplanted agricultural zoning, encroaching the neighborhood. At most, 150 residents live there now.

Despite being Joppa Preserve’s central feature, Lemmon Lake is now a mud flat most of the year due to a busted embankment never repaired. Good luck even finding the preserve entrance or the Eco Park trailhead for Trinity Forest Trails.

Neither have directional signs on SH 310.

Five Mile Creek, another natural centerpiece of the community, was re-routed and channelized during the McCommas Bluff Landfill creation. When it opened in the early 1980s, the landfill became the area focus, not the historic communities of color.

Floral Farms residents don’t hope to recoup an unattainable, possibly romanticized, past. Many of them own or work at industrial plants nearby.

But Evelyn Mayo, a fellow at Paul Quinn’s Urban Research Initiative and board chair of Downwinders at Risk, said, in Dallas, industrial zoning is synonymous with neglect.

“It would be one thing to have correct zoning procedures and enforcement. But that’s not the case here.“

Dismissed as deluded for holding on to their heritage amid an industrial onslaught, Floral Farms persists.

Even as Shingle Mountain loomed, the Garcia family pavilion next to Jackson’s house continued to host birthday parties, quinceañeras and weddings. Every Dec. 12, the Catholic faithful gather for procession adoring the Virgin of Guadelupe — the heart of a Latinx community.

SHUTTING DOWN SHINGLE MOUNTAIN

Jackson moved to Floral Farms in the 1990s, drawn by the ability to keep horses, a generational family tradition, on land zoned as agricultural. She held down a downtown job, the commute was short, and the land around her was lushly wooded.

Then in 2018, the shingle grinding started behind her house on Choate Road, sometimes as early as 5 a.m. Even though agriculturally zoned land can have residences, noise-abatement regulations that residential-zoned areas enjoy do not apply.

Video from Downwinders at Risk shows the shocking images of Shingle Mountain from the neighbors’ perspective.

While the company, Blue Star Recycling, claimed to be prepping shingles for recycling into asphalt paving, much more material came in than went out, and the mountain grew.

The mountain sprawled from the main site, a four-acre plot facing SH 310, across a creek to a two-acre site to the north at the corner of Choate. The debris backed up stormwater and flooded Jackson’s stables, forcing her to relocate the horses.

Jackson and other nearby Floral Farm residents began to suffer neurological and respiratory illnesses from the shingle dust, compounded by McCommas Bluff Landfill, another source of particulate matter pollution.

FIGHT OVER FLIGHT

As an asbestos-infused mountain of shredded shingles rose, so did an activist coalition. Jackson and her Floral Farms neighbors formed Neighbors United/Vecinos Unidos, a neighborhood association.

Other allied organizations include Inclusive Communities Project headed up by Jennifer Rangel, Paul Quinn College, Southern Sector Rising and Downwinders at Risk.

After years of pressure from activists, the city shut down Blue Star and took possession of the main acreage. The city received the land for free plus a $1 million settlement to remove over 150,000 tons of material. But removal cost only $450,000. Activists are seeking to uncover where the remaining funds went.

After the removal was completed in mid February last year, tests of soil beneath the mountain revealed up to 1,450 parts per million of lead. That level meets commercial/industrial land use standards, but not residential standards. According to the Environmental Protection Agengy and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there is no safe level of lead for children — worrisome for families with children living or visiting on Choate Road.

As for the two acres not yet purchased by the city, the owner of the property, Almira Industrial, did their removal and partial remediation, circumventing city shutdown. A new permit was recently issued allowing machinery, heavy equipment and truck operations.

Residents wanted the acreage downzoned to less industrial uses.

“The hearing for rezoning the whole community was placed on the list two years ago, and has been stuck at 12 [out of 16] on the list since then,” said Mayo. “Residents are working with the planning department on getting it expedited to the top so that they don’t have to keep playing Whac-A-Mole with industry and the City Planning Commission. So they can just have the zoning they need to thrive.”

A PARK IS (ALMOST) BORN

What to do with four-plus acres of toxic, but remediable city-owned land? The Floral Farms activists’ demands are straightforward: make a regional park.

Inspired by the activists, and Jackson being a finalist for Dallas Morning News’ Texan of the Year, architectural design firm HKS stepped in.

Through its Citizen HKS initiative for public-interest design work, the firm unveiled a plan last December after working with residents for over a year to visualize the park design.

Citizen HKS plans call for an arched entry with the words “Together We Can Move Mountains” and a 14-foot-tall grassy hill to evoke the former Shingle Mountain, complemented by playing fields, picnic areas, walking paths and plentiful trees.

The concept won the 2021 Greater Dallas Planning Council Urban Design Award for Unbuilt Dream/Study. Santander Bank Consumer Foundation, Dallas Regional Chamber and Dallas Stars Foundation are poised to help fund the project. Individual donations are encouraged as well.

“The park is not a pipe dream,” said Mayo. “It’s actually one of the only ways we can make sure this site is permanently protected. By rezoning it to residential use, which allows a park, there would be whole remediation. We’re in discussion with the city, the councilman, and the environmental committee, on what their intentions are for this site, and whether they’re willing to engage in a public-private partnership to make this park real.”

“In June 2021, Council voted to acquire the land,” continued Mayo. “Since then, there has been no public engagement around future land use that’s been city driven. So we are now engaging them again: ‘You’re the property owner. We have this neighborhood plan. We have this authorized hearing process for rezoning this neighborhood. We need an update on how you plan to partner with us.’ So, the ball’s really in the city’s court.”

Inspiring video showcases concepts for the potential Floral Farms park. Courtesy of HKS.

THE TRAILS THAT BIND US

Floral Farms activists consider the park key to revitalizing not only their neighborhood, but the Great Trinity Forest’s west side.

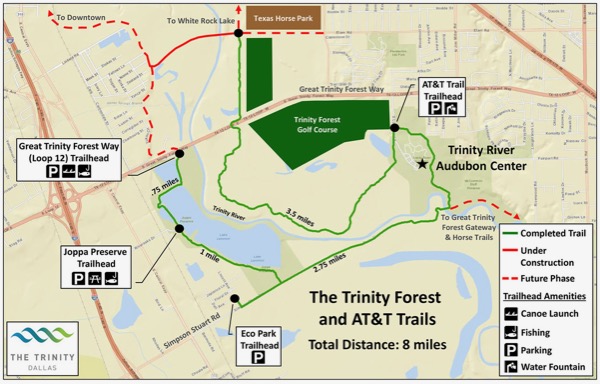

Joppa Preserve and the Eco-Park trailhead for Trinity Forest Trail are a mile as the crow flies. The old Fin and Feather Club acreage, purchased last year by the city of Dallas for parkland, is barely more than two miles.

Between those is two square miles of McCommas Bluff Landfill, which has only a few decades of life remaining. Once the landfill closes, many of the adjoining scrap industries will have little motivation to remain.

Mayo noted that federal funds for remediating polluted brownfields such as landfills into greenspace would be possible to obtain.

The addition of green space would have an economic benefit to Dallas. The Proximate Principle, developed by John L. Crompton of Texas A&M, asserts that the presence of parks and undeveloped nature near residential land increases its value and thus grows a municipality’s tax base.

That principle is a motivating factor behind Trust for Public Land’s sprawling south Oak Cliff greenbelt vision.

The west side of the Great Trinity Forest is bounded mainly by industry. The northern part of the wedge between SH 310 and I-45 is entirely concrete.

But south of Simpson Stuart, an outlier of the Great Trinity Forest remains, home to Five Mile Creek’s original channel. Wells Fargo owns much of it. Alongside those woods runs an electric utility corridor — perfect for a trail that routes Floral Farms residents and others into the park without risk of vehicle encounters on busy SH 310.

“The real connector piece, though,” said Mayo, “is the trailway connections of The Loop, which is trying to do 50 miles of trails connecting the whole city. The Trust for Public Land and their Five Mile Creek Urban Greenbelt Trail will cut right through here and connect to the Trinity River. By putting a park here, we become the southernmost anchor of this new connectivity.”

ECO RACISM BY ZIP CODE

If the story of local environmental racism sounds familiar, it is. The African-American residents of Deepwood in southeast Dallas fought the city of Dallas for over two decades. Illegal dumping in the Great Trinity Forest adjacent to them was so extreme, tire fires twice spewed toxic smoke over their homes for weeks. Federal courts finally found in the residents’ favor and forced action. One end result was the Trinity River Audubon Center

In West Dallas, GAF’s asphalt shingle factory polluted the neighborhood for over three decades without air quality permits and little city or state regulatory oversight.

Meanwhile, concrete batch plants, which generate extreme amounts of particulate pollution and industrial noise, are often pushed upon minority communities. Floral Farms residents have fought three since 2018.

States a Dallas Morning News editorial, “This chasm is most tangibly measured in investment, income, health care and employment disparities. Roughly 45 percent of the city’s residents live in southern Dallas, but those neighborhoods make up only 15 percent of the tax base. Residents of southern Dallas neighborhoods also have a lower median household income and worse health outcomes.”

Yet there are no EPA air monitors in Floral Farms, Joppa, or West Dallas, according to Downwinders at Risk, just on adjacent highways. Downwinders stepped in with portable air monitors in these areas.

MILESTONES

In times like these, activism turns to art for conveying complex, emotionally charged issues. The Dallas Museum of Art’s Center for Creative Connections presents Rooted through April 9, 2023. The exhibit includes Poisoned by Zip Code, an installation that highlights Jackson’s fight for environmental justice in the Floral Farms neighborhood.

Last year, Dallas County Commissioners Court officially declared Feb. 22 to be Marsha Jackson Day, commemorating the removal of Shingle Mountain, coinciding with Jackson’s birthday. One-year anniversary celebrations are planned starting with a Block Party on Feb. 21, a panel discussion on March 5 at the Dallas Museum of Art, and a Dallas Stars Hockey Game dedicated to the park project on March 26. Check the Neighbors United Facebook page for details.

Downtown Dallas gleams like a shining city on Trinity River bluffs to those looking north on SH 310, the old S. Central Expressway. But is that glittering promise also for those south of I-30? What will it take to realize the lost potential of Floral Farms and its Great Trinity Forest heritage?

“Persistence pays,” said Mayo. “That’s our motto.“

RELATED ARTICLES

Shingle Mountain move is underway

Activists keep pressure on city as it takes steps to move Shingle Mt

Researchers aim to chronicle environmental injustice in Dallas

Film recounts how Dallas Audubon Center rose from illegal dump site